by Zulfikar Fahd

JK Rowling used to be a childhood hero for many millennials. This year, the once beloved writer came out as transphobic—hence she has joined tens of other public figures and brands who got “cancelled” in recent years. This trend that was started on social media, known as “cancel culture”, is where a truckload of internet users combines efforts to withdraw support for those who have said or done something deemed as offensive. In many cases, these cancellations amount to piling shame on the perpetrators, boycotting their products or services, and may even lead to the firing of the individuals involved.

Today’s society grows increasingly “woke”, and the cancel culture reflects this phenomenon. It has been a powerful tool for those who have long been powerless against public figures and entities that compound widespread injustice, inequality, and prejudice. On the other hand, it can be a reflexive crusade where the goal is simply feeling a sense of righteousness and emotional satisfaction at taking down someone who was not as “woke”, both socially and politically.

In the last few months during the heated political tension experienced by our southern neighbour, Goya Foods had been canceled by liberals in the US as their CEO publicly showed support for President Trump; and Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream had been canceled by the conservatives as they have been very vocal on Black Lives Matter and Defund the Police movements.

While this is especially visible in countries with a strong activist history, such as the United States, social media and the internet have made it a worldwide trend. In Canada, for example, Prime Minister Trudeau met a backlash when an old photo of him in Black face resurfaced. Many called for his resignation based on this past behaviour.

In a world that is outwardly so quick to take offense, should companies and brands even try to have a social purpose? Or should businesses stick to business as usual?

Do businesses need a social purpose beyond profit?

Take a look at The Body Shop’s “Enrich, Not Exploit” purpose. It answers customers’ demands for ethically made and sustainably sourced beauty products by, among others, pioneering fair trade, campaigning against animal-testing, and introducing a recycled plastic initiative. These have provided the brand with a loyal customer base around the world. This is a social purpose that revolves around not only selling a specific product or service, but also answering specific needs of the communities the business serves.

I would argue that businesses in general need a social purpose, and this could be an effective marketing weapon. The days where businesses’ sole responsibility is to the shareholders are gone now. Today, employees and customers share more power to influence business success, and what they want is businesses that promote the well-being of the society.

The social purpose defines why the business exists, informs their values and culture, provides context for strategy and decision making, and motivates stakeholders. If genuine and meaningful, it gives the brands legitimacy especially in today’s woke world.

Recent studies by Gallup and Nielsen found businesses that are driven by purpose, rather than by generating profit for shareholders, tend to outperform others.

Translating social purpose into marketing

Once purpose is defined, many companies and brands may find it tempting to introduce only low-cost, cosmetic changes that give them quick bragging rights in their splashy marketing efforts.

Businesses should not fall into this trap.

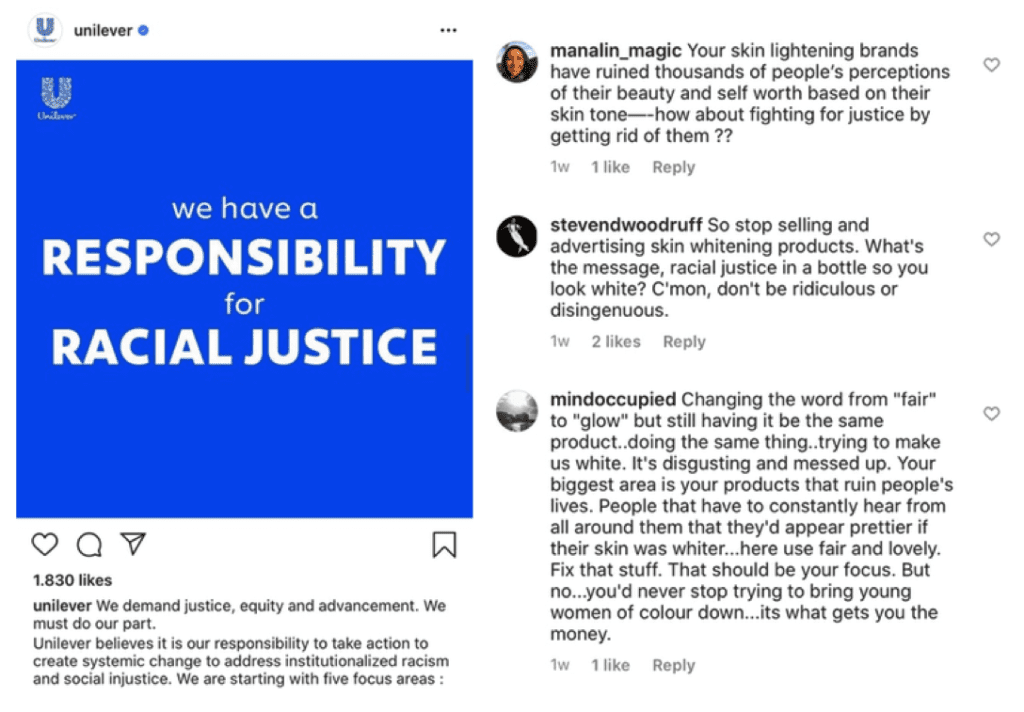

Companies would do well to learn from Unilever that recently tried to be “woke” on Black Lives Matter causes, only to be tripped up by the fact that it continues to market the “Fair and Lovely” skin-lightening cream, especially to the Asian market. It was slammed by critics for its perceived hypocrisy. Unilever thought it would go away with simply rebranding the product to “Glow & Lovely” in India. Instead, it was “cancelled” for not doing enough while still reaping profits from a product deemed as problematic.

Contrast this with Johnson & Johnson who pledged to stop selling skin-lightening products altogether.

Once companies have defined their social purpose, their ever-going homework is to consistently articulate and translate it into effective marketing. This means delivering it across all their touch points and ensuring that it is essential to their culture. If they stand for inclusivity, they should look inside and check whether their recruitment is diverse, whether they have anti-discrimination policies in place, and whether they unconsciously alienate certain parts of their communities in the way they price or market their products.

Only then are they not simply using social purpose for sales, but instead it will naturally be infused into everything they do, including their marketing efforts and how they communicate in public realms.

Remember what happened to Starbucks a couple of years ago? Its social purpose is “to inspire and nurture the human spirit–one person, one cup, and one neighborhood at a time”, but then it got into hot water when two Black men were arrested at a Starbucks in Philadelphia after the store manager racially profiled and called the police on them. This led some to mock Starbucks’ purpose statement. Instead of being defensive, the CEO swiftly harnessed the transformative power that Starbucks’ purpose already had. He swiftly acknowledged what the company could have done better and took action to nurture awareness of racial bias among its employees. Today, the company continues to add its voice to conversations around racism.

While it may be debatable whether cancel culture should be canceled, having a social purpose beyond profit and consistently articulating it will arguably save companies a lot of potential headaches.

If they intentionally choose a social purpose that reflects how their business wants to evolve, it can have a tremendous transformative impact. It drives employees, unites stakeholders, and inspires public goodwill toward their business. That is the true power of social purpose, even–or especially–in the “cancel culture” era.